Malaria is the world’s second most common disease causing over 500 million infections and one million deaths every year. Worryingly it is one of those diseases which is beginning to increase as it develops resistance to treatments. Even in the UK, where malaria has been effectively eradicated, more than 2,000 people are infected as they return from trips abroad and the numbers are rising.

It seems as though malaria has been in existence for millions of years and a similar disease may have infected dinosaurs. Malaria-type fevers are recorded among the ancient Greeks by writers such as Herodotus who also records the first prophylactic measures: fishermen sleeping under their own nets. Treatments up until the nineteenth century were as varied as they were ineffective. Live spiders in butter, purging and bleeding, and sleeping with a copy of the Iliad under the patient’s head are all recorded. The use of the first genuinely effective remedy, an infusion from the bark of the cinchona tree, was recorded in 1636 but it was only in 1820 that quinine, the active ingredient from the cinchona bark was extracted and modern prevention became possible. For a long time the treatment was regarded with suspicion since it was associated with the Jesuits. Oliver Cromwell, the Protestant English leader who executed King Charles I, died of malaria as a result of his doctors refusing to administer a Catholic remedy! Despite the presence of quinine, malaria was still a major cause of illness and death throughout the nineteenth century. Hundreds of thousands were dying in southern Europe even at the beginning of the last century. Malaria was eradicated from Rome only in the 1930s when Mussolini drained the Pontine marshes.

Despite the fact that malaria has been around for so long, surprisingly little is known about how to cure or prevent it. Mosquitoes, who are the carriers of the disease, are attracted to heat, moisture, lactic acid and carbon dioxide but how they sort through this cocktail to repeatedly select one individual for attention over another is not understood. It is known that the malaria parasite, or plasmodium falciparum to give it its Latin name, has a life cycle which must pass through the anopheles mosquito and human hosts in order to live. It can only have attained its present form after mankind mastered agriculture and lived in groups for this to happen. With two such different hosts, the life cycle of the parasite is remarkable.

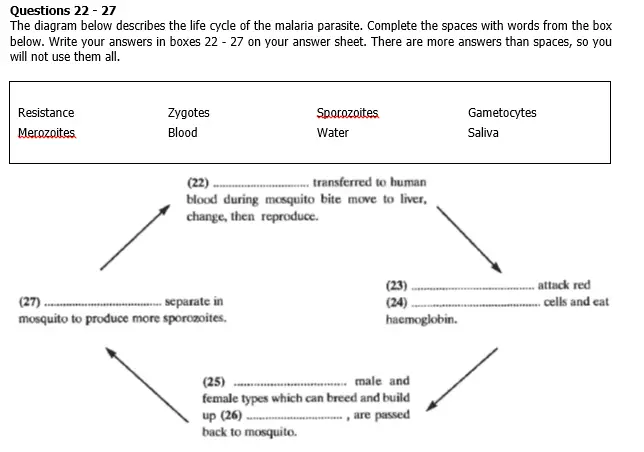

There is the sporozoite stage which lives in the mosquito. When a human is bitten by an infected anopheles mosquito the parasite is passed to the human through the mosquito’s saliva. As few as six such parasites may be enough to pass on the infection provided the human’s immune system fails to kill the parasites before they reach the liver. There they transform into merozoites and multiply hugely to, perhaps, about 60,000 after 10 days and then spread throughout the bloodstream. Within minutes of this occurring, they attack the red blood cells to feed on the iron-rich haemoglobin which is inside. This is when the patient begins to feel ill. Within hours they can eat as much as 125 grams of haemoglobin which causes anaemia, lethargy, vulnerability to infection, and oxygen deficiency to areas such as the brain. Oxygen is carried to all organs by haemoglobin in the blood. The lack of oxygen leads to the cells blocking capillaries in the brain and the effects are very much like that of a stroke with one important difference: the damage is reversible and patients can come out of a malarial coma with no brain damage. Merozoites now change into gametocytes which can be male or female and it is this phase, with random mixing of genes that results, that can lead to malaria developing resistance to treatments. These resistant gametocytes, can be passed back to the mosquito if the patient is bitten, and they turn into zygotes. These zygotes divide and produce sporozoites and the cycle can begin again.

The fight against malaria often seems to focus on the work of medical researchers who try to produce solutions such as vaccines. But funding is low because, it is said, malaria is a third world condition and scarcely troubles the rich, industrialised countries. It is true that malaria is, at root, a disease of poverty. The richer countries have managed to eradicate malaria by extending agriculture and so having proper drainage so mosquitoes cannot breed, and by living in solid houses with glass windows so the mosquitoes cannot bite the human host. Campaigns in Hunan province in China, making use of pesticide impregnated netting around beds reduced infection rates from over 1 million per year to around 65,000. But the search for medical cures goes on. Some 15 years ago there were high hopes for DNA based vaccines which worked well in trials on mice. Some still believe that this is where the answer lies and shortly too. Other researchers are not so confident and expect a wait of at least another 15 years before any significant development.

Questions 14-21

Do the following statements agree with the information in Reading Passage 2? In boxes 14 – 21 on your answer sheet write

YES if the statement agrees with the information

NO if the statement contradicts the information

NOT GIVEN if there is no information on this in the passage.

14 Malaria started among the ancient Greeks.

15 Malaria has been eradicated in the wealthier parts of the world.

16 Mosquitoes are discerning in their choice of victims.

17 Treatments in the nineteenth century were ineffective

18 Iron is a form of nourishment for malarial merizoites.

19 A severe attack of malaria can be similar to a stroke.

20 Research into malaria is not considered a priority by the West.

21 Technological solutions are likely to be more effective than low-tech solutions.