Earthworms are not creatures likely to attract much attention. Socretive, silent, slow-moving, and featureless, almost no one would ever think. Let’s quote Charles Darwin, who wrote: ‘It may be doubted wheather there are many other animals whichs have played so important a part in the history of the world as have these lowly-organised creatures’.

That is high praise indeed for what is basically a slimy, muscular, moist, segmented tube. This tube is also hermaphroditic, meaning that there are both male and female segments in the one creature. Some segment contain testes, others eggs, released ooze, exchange, and store fluids, and then a long complicated process eventually leads to the secretion of an egg case. From this, small but fully-formed worms will emerge, reaching full size in about one year, and living for one or two years after that.

Yet earthworms are rarely seen, spending as they do their whole lives underground. Only after heavy rains can they sometimes be found on the surface, apparently stranded. Three hypotheses are put forward to explain this. The stormwater may flood their burrows, forcing them upwards. Alternatively, the worms may be taking advantage of the wet conditions to either travel more quickly through the open air (compared to burrowing beneath the ground), or otherwise to meet and mate. Whatever the case, if they find themselves on concreted, rocky, or hardened earth, they are effectively trapped. If this is during dawn, in high summer, or in the daytime, these earthworms quickly die due to bird predation or dehydration.

Normally, however, worms quietly go about their hidden business, and this often leads to an underestimation of their actual numbers. Darwin himself thought that arable land contained about 50,000 worms per acre, yet modern research has suggested that the figure could reach as high as almost two million. Putting this another way, the weight of earthworms beneath the soil is often greater than that of the cows, horses, and sheep are zing upon is surface. And those worms are just as hungry. Worms do, in fact, have a small mouth and a simple but effective digestive system, similar to the animals above, Food is sucked into the body, then pushed along the length of the worm through muscular action, passing through the crop, gizzard, intestine, and finally the anus.

Perhaps surprisingly, it is this constant eating which so benefits the chemistry of the soil. Earthworms feed on undecayed leaf litter and organic matter. They pull pieces down into their burrows, shred them into smaller parts, and then consume each of these, along with small soil particles. In the worms’ gut, everything is ground into a a fine paste, to be eventually excreted , releasing essential minerals in an easily accessible form. One single worm may produce over four kilograms of this digested paste per year. Multiply that by a million worms, and one can understand Darwin’s comment about ‘unsung creatures which, in their untold millions, transformed the land’.

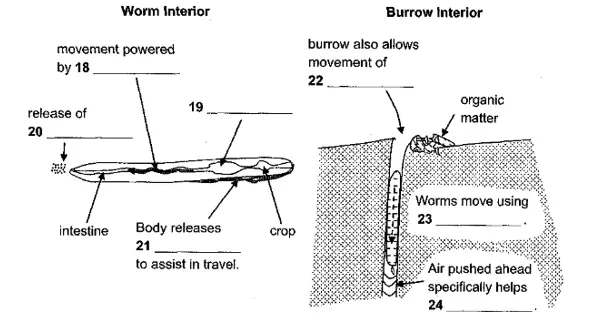

The other great benefit relates to earthworms’ search for food. It might surprise many to know that these creatures are very mobile, moving to the surface then down into the safer depths on a daily basis. Aided by the secretion of lubricating mucus, they push themselves through the soil using waves of bodily contractions, which alternately shorten and lengthen their form. The point is, water can also move through their tunnels. More importantly, as the worms travel, they push air in and out of the soil on a continuous basis. In the same way that animals need oxygen, so too do the myriad micro-organisms in the soil. Thus, without worms, the ground would become waterlogged, airless, and less productive for farming purposes.

Naturally, with so many worms in the soil, they form the base of many food chains. Not only birds, but also some mammals, such as hedgehogs, moles, and even larger ones, such as foxes and bears, will actively dig into the ground of worms. Such predation is natural, and has little effect on worm populations. However, the use of certain fertilisers is a different case. Earthworms depend on the temperature, texture, and moisture content of the soil, but it is its acidity to which they are most sensitive. Nitrogenous fertilisers can raise this to levels fatal to these creatures, often causing disastrous drops in numbers. The more ecologically-aware farmer avoids such chemicals, and regularly adds a surface mulch of organic matter raising worm numbers for the natural benefit of both soil and man.

Questions 14-17

Choose the correct letter, A, B, C, or D.

14. Charles Darwin thought that worms

A were only moderately important.

B were organised.

C liked arable land.

D numbered in the many millions.

15. A single worm

A is either male or female.

B has many segments.

C is a complicated organism.

D lives for about a year.

16. Stormwater may possibly

A clean out worm burrows.

B slow down worms.

C help worms encounter others.

D harden the earth.

17. Grazing animals

A often weigh less than the worms below.

B are hungrier than the worms below.

C have very different digestive systems from worms.

D have simpler digestive systems than worms.

Questions 18-24

Complete the diagram. Choose NO MORE THAN TWO WORDS from the passage for each answer.

Questions 25-26

Complete the sentences. Choose NO MORE THAN TWO WORDS from the passage for each answer.

Worm numbers will especially fall when the soil has high (25)………………..

Adding mulch to the soil shows (26)……………………..